The Brussels II Regulation 2003

Section 3 (Chapter II) Common provisions for determining jurisdiction

Besides the recognition and enforcement of judgments, the Brussels II Regulation determines which Member State has jurisdiction over international disputes and relationships concerning the ending of a marriage and parental responsibility, including child abduction. The term ‘jurisdiction’ refers to the authority given by law to a court to try cases and rule on legal matters within a particular geographic area and/or over certain types of legal cases. At international lawsuits on these specific matrimonial matters between citizens of two different EU Member States, the law which determines at which court a lawsuit can be filed, is the Brussels II Regulation 2003.

In fact the Brussels II Regulation 2003 encloses four different kind of rules to establish which Member State(s) has (have) jurisdiction over matrimonial matters as mentioned above. That’s why first of all the question must be answered what kind of legal action exactly is or will be started, since the Regulation distinguished between:

- actions to accomplish a divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment;

- actions on the basis of parental responsibility;

- actions after a child has been abducted;

- actions to protect the property of the child, provided the aim is to protect the child itself.

The scope of the Brussels II Regulation is, compared to its forerunner, the Brussels II Regulation 2000, extended to all civil proceedings relating to parental responsibility by cutting the link with the matrimonial proceedings. However, matters relating to maintenance are excluded, as these are already covered by the Brussels I Regulation 2000 on jurisdiction over civil and commercial matters (Council Regulation (EC) No 44/2001).

The Brussels II Regulation (Article 20 BR II) enables a court to take provisional, including protective, measures in accordance with its national law in respect of a child situated on its territory even if a court of another Member State has jurisdiction as to the substance of the application. The measure can be taken by a court or by an authority having jurisdiction in matters falling within the scope of the Regulation. A welfare authority or a youth authority may, for instance, be competent to take provisional measures under national law. Article 20 BR II is not a rule which confers jurisdiction. Consequently, the provisional measures cease to have effect when the competent court has taken the measures it considers appropriate.

The courts of the Member States have to look upon certain rules when confronted with a request or lawsuit that falls under the scope of the Brussels II Regulation. This ensures that the same procedure will be followed in the entire European Union.

Article 16 of the Brussels II Regulation

Seising of a court [Article 16 BR II]

Article

16 Seizing of a court |

The first question that has to be answered is at what time a legal proceeding is regarded to be started officially. This answer is important in order to establish whether the same request or lawsuit is filed twice, before different courts.

Article 16 BR II distinguishes two separate starting points.

A court shall be deemed to be seised at the time when the document instituting the proceedings or an equivalent document is lodged with the court, provided that the applicant has not subsequently failed to take the steps he was required to take to have service effected on the respondent.

But a court shall also be deemed to be seised if the document has to be served before being lodged with the court, at the time when it is received by the authority responsible for service, provided that the applicant has not subsequently failed to take the steps he was required to take to have the document lodged with the court.

Article 17 of the Brussels II Regulation

Examination of its own motion as to jurisdiction [Article 17 BR II]

![]()

Article

17 Examination of its own motion as to jurisdiction |

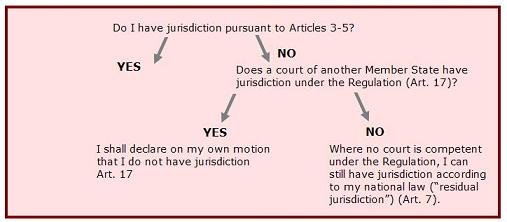

Internal legal systems are particularly sensitive to matrimonial matters, more sensitive than they are to the property matters covered by the 1968 Brussels Convention and the Brussels I Regulation. That’s why it was felt necessary to stipulate that the courts of the Member States, to whom a request or lawsuit is presented, automatically examine if they have jurisdiction or not, without any need for any party to request it. Where a court of a Member State is seised of a case over which it has no jurisdiction under the Brussels II Regulation 2003 and over which a court of another Member State has jurisdiction by virtue of this Regulation, it shall declare of its own motion that it has no jurisdiction (Article 17 BR II).

‘Bearing in mind the major differences between internal regulations in the Member States and the interplay of choice-of-law rules applicable, it is easy to imagine that the fact that the grounds of jurisdiction set out in [Article 3 BR II 2003] are alternatives may lead some spouses to attempt to make their application in matrimonial matters before the courts of a State which, by virtue of its choice-of-law rules, applies the legislation most favourable to their interests. For that reason, the court first seised must examine its jurisdiction, which might not happen if the issue were discussed in that Member State only as an exception’ (Borras (1998) C 221/45)

See also the following Scheme

According to the clear wording of Article 7, paragraph 1, BR II, it is only where no court of a Member State has jurisdiction pursuant to Articles 3 to 5 of the Brussels II Regulation that jurisdiction is to be governed, in each Member State, by the laws of that State. Moreover, according to Article 17 BR II, where a court of one Member State is seised of a case over which it has no jurisdiction under that regulation and a court of another Member State has jurisdiction pursuant to that regulation, it is to declare of its own motion that it has no jurisdiction. That interpretation is not affected by Article 6 BR II, since the application of Articles 7, paragraph 1, and 17 BR II depends not upon the position of the respondent, but solely on the question whether the court of a Member State has jurisdiction pursuant to Articles 3 to 5 of the Regulation, the objective of which is to lay down uniform conflict of law rules for divorce in order to ensure a free movement of persons which is as wide as possible. Consequently, the Brussels II Regulation applies also to nationals of non-Member States whose links with the territory of a Member State are sufficiently close, in keeping with the grounds of jurisdiction laid down in that regulation, grounds which are based on the rule that there must be a real link between the party concerned and the Member State exercising jurisdiction (ECJ 29 November 2007 ‘Kerstin Sundelind Lopez v Miguel Enrique Lopez Lizazo’, Case C-68/07).

Article 18 of the Brussels II Regulation

Examination as to admissibility [Article 18 BR II]

Article

18 Examination as to admissibility |

The right of defence of a party has to be guaranteed. Therefore it is not sufficient to examine jurisdiction alone, as provided for in Article 17 BR II. It is also necessary to establish a similar rule for examining admissibility, involving staying the proceedings so long as it is not shown that the respondent has been able to receive the document instituting the proceedings or an equivalent document in sufficient time to enable him to arrange for his defence, or that all necessary steps have been taken to this end. The intention is that the court can satisfy itself that international jurisdiction is well founded and so avoid possible causes of refusal of recognition wherever possible. (Borras (1998) C 221/45)

‘Where a respondent habitually resident in a State other than the Member State where the action was brought does not enter an appearance, the court with jurisdiction shall stay the proceedings so long as it is not shown that the respondent has been able to receive the document instituting the proceedings or an equivalent document in sufficient time to enable him to arrange for his defence, or that all necessary steps have been taken to this end’ (Article 18, paragraph 1, BR II).

Article 18 BR II is based on Article 20 of the 1968 Brussels Convention and, on the same topic, the provisions in the 1965 Hague Convention on the service abroad of judicial and extrajudicial documents in civil or commercial matters. The court, when applying one of the grounds of jurisdiction provided for in the Brussels II Regulation, will examine its jurisdiction where the respondent does not enter an appearance. The wording adopted is simpler than in other Conventions but the essential elements are covered:

- an obligation on the court to stay proceedings, not merely an option;

- the respondent’s rights of defence to be examined by the court, both as to whether he has been able to receive the document ‘in sufficient time to enable him to arrange for his defence’ and as to whether ‘all necessary steps have been taken to this end’.

Article 19 of Regulation (EC) No 1348/2000 shall apply instead of the provisions of paragraph 1 of this Article if the document instituting the proceedings or an equivalent document had to be transmitted from one Member State to another pursuant to that Regulation (Article 18, paragraph 2, BR II). The Directive on the service in the Member States of the European Union of judicial and extrajudicial documents in civil or commercial matters will replace the provisions described in paragraph 2 once it is transposed by the Member States. Until then, the provisions of the Hague Convention of 15 November 1965 on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters will apply if the document instituting the proceedings has had to be transmitted abroad in pursuance of the Directive. (COM/99/0220 final - CNS 99/0110 / Official Journal C 247 E , 31/08/1999). This is regulated in paragraph 2 and 3 of Article 18 BR II.

‘The recent signing of the Convention of 26 May 1997 on the service in the Member States of the European Union of judicial and extrajudicial documents in civil or commercial matters has led to a provision that, once it has entered into force, Article 19 thereof will be applied instead of the provisions in paragraph 1. Bearing in mind the possibility of the early application of the 1997 Convention, there will be a gradual substitution of the European Community Convention for the Hague Convention and there will not, therefore, be a general entry into force. As Articles 15 and 16 of the Hague Convention are reproduced in the 1997 Convention the change of Convention applicable will not entail any significant changes’ (Borras (1998) C 221/45).

Article 19 of the Brussels II Regulation

Lis pendens and dependent actions [Article 19 BR II] ![]()

Article

19 Lis pendens and dependent actions |

It may happen that the same parties initiate court proceedings on the matters of the same divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment or on matters of parental responsibility concerning the same child and the same cause of action in different Member States. This may result in parallel actions and consequently the possibility of irreconcilable judgments on the same issue. Article 19 BR II provides a mechanism whereby the court second seized declines its jurisdiction in favor of the court first seized. It was felt necessary to give a rule for situations in which the same cause of action has been brought to the courts of two or more different Member States. The difference in rules governing matrimonial proceedings in the Member States raises the need for changes to the lis pendens rules in the Brussels Convention of 1968. In particular, certain Member States have no provision for annulment of marriage or for judicial separation. The difference in rules between the Member States also affects the very notion of lis pendens. The notion is more restricted in some States, requiring the same subject-matter, the same cause of action and the same parties, and broader in others, which require only the same cause of action and the same parties.

‘The difference in rules between the Member States also affects the very notion of lis pendens. The notion is more restricted in some States (France, Spain, Italy and Portugal) requiring the same subject-matter, the same cause of action and the same parties, and broader in others which require only the same cause of action and the same parties. The lis pendens mechanism is designed to avoid parallel actions and consequently the possibility of irreconcilable judgments on the same issues and the objective was to provide a rule which, on the basis of the basic principle of prior temporis, could provide a solution for the various possibilities in family law, which differ from those in property law. The traditional lis pendens arrangement did not solve all the problems and there was therefore a need to find a new wording which would achieve the objective desired. After lengthy discussion, it was the Luxembourg Presidency which proposed the text finally accepted by the Member States’ (Borras (1998) C 221/46).

As regards proceedings relating to divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment, the mechanism is triggered if these are between the same parties. ‘Where proceedings relating to divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment between the same parties are brought before courts of different Member States, the court second seised shall of its own motion stay its proceedings until such time as the jurisdiction of the court first seised is established’ (Article 19, paragraph 1, BR II).

‘53. Paragraph 1 contains the traditional lis pendens rule, that is to say the prior temporis rule applicable to all proceedings covered by the [Regulation], provided the subject-matter and cause of action are the same between the same parties. To avoid the risk of negative conflict of jurisdiction, it is stipulated that the court second seised shall of its own motion stay its proceedings until such time as the jurisdiction of the court first seised is established’ (Borras (1998) C 221/46).‘Once a court has been seised pursuant to Article 3 of the Regulation and declared itself competent, courts of other Member States are no longer competent and must dismiss any subsequent application. The aim of the “lis pendens” rule is to ensure legal certainty, avoid parallel actions and the possibility of irreconcilable judgments.

The wording of Article 19(1) has been modified slightly compared to Article 11(1) and (2) of the Brussels II Regulation [2001]. The change was introduced to simplify the text without changing the substance.

Article 19(1) covers two situations:

(a) Proceedings relating to the same subject-matter and cause of action are brought before courts of different Member States and;

(b) Proceedings which do not relate to the same cause of action, but which are

“dependent actions” are brought before courts of different Member States (Practice Guide 2005, p. 49).

As regards proceedings relating to parental responsibility, the mechanism is triggered if these involve matters of parental responsibility over the same child. It is expected that this will rarely be used, as the jurisdictional regime for parental responsibility does not provide for alternative grounds of jurisdiction. ‘Where proceedings relating to parental responsibility relating to the same child and involving the same cause of action are brought before courts of different Member States, the court second seised shall of its own motion stay its proceedings until such time as the jurisdiction of the court first seised is established’ (Article 19, paragraph 2, BR II).

‘Article 19(2) regulates the situation where proceedings relating to parental responsibility are brought in different Member States concerning:

- the same child and

- the same cause of action

In that situation, Article 19(2) stipulates that the court first seised is, in principle,

competent. The court second seised has to stay its proceedings and wait for the other court to decide whether it has jurisdiction. If the first court considers itself competent, the other court must decline jurisdiction. The second court may only continue its proceedings if the first court comes to the conclusion that it does not have jurisdiction or if the first court decides to transfer the case pursuant to Article 15.

It is expected that the lis pendens mechanism will be rarely used in proceedings relating to parental responsibility since the child is usually habitually resident in only one Member State in which the courts have jurisdiction according to the general rule of jurisdiction (Article 8).

The Regulation provides for another way of avoiding potential conflicts of jurisdiction by allowing a transfer of the case. Hence, Article 15 allows a court, as an exception and under certain conditions, to transfer a case, or a part thereof, to another court (see chapter III)’ (Practice Guide 2005, p. 22).

The provisions of Article 19, paragraph 2, BR II are not applicable where a court of a Member State first seised for the purpose of obtaining measures in matters of parental responsibility is seised only for the purpose of its granting provisional measures within the meaning of Article 20 of that Regulation and where a court of another Member State which has jurisdiction as to the substance of the matter within the meaning of the same regulation is seised second of an action directed at obtaining the same measures, whether on a provisional basis or as final measures. The fact that a court of a Member State is seised in the context of proceedings to obtain interim relief or that a judgment is handed down in the context of such proceedings and there is nothing in the action brought or the judgment handed down which indicates that the court seised for the interim measures has jurisdiction within the meaning of the Brussels II Regulation does not necessarily preclude the possibility that, as may be provided for by the national law of that Member State, there may be an action as to the substance of the matter which is linked to the action to obtain interim measures and in which there is evidence to demonstrate that the court seised has jurisdiction within the meaning of that regulation. Where, notwithstanding efforts made by the court second seised to obtain information by enquiry of the party claiming lis pendens, the court first seised and the central authority, the court second seised lacks any evidence which enables it to determine the cause of action of proceedings brought before another court and which serves, in particular, to demonstrate the jurisdiction of that court in accordance with the Brussels II Regulation, and where, because of specific circumstances, the interest of the child requires the handing down of a judgment which may be recognised in Member States other than that of the court second seised, it is the duty of that court, after the expiry of a reasonable period in which answers to the enquiries made are awaited, to proceed with consideration of the action brought before it. The duration of that reasonable period must take into account the best interests of the child in the specific circumstances of the proceedings concerned (ECJ 9 November 2010 ‘Bianca Purrucker v Guillermo Vallés Pérez’, Case C-296/10).

Paragraph 3 of Article 19 BR II sets out the consequences of the acceptance of jurisdiction by the court first seised. The provision contains a general rule, which is that the court second seised shall decline jurisdiction in favour of that court. It also contains a special rule whereby the party who brought the relevant action before the court second seised may, if he so wishes, bring that action before the court which claims jurisdiction because it was seised earlier. The first words in the second paragraph of paragraph 3, 'in that case', must therefore be interpreted as meaning that only when the court second seised declines jurisdiction does the party have the possibility of bringing the action before the court having claimed jurisdiction because it was first seised. (COM/99/0220 final - CNS 99/0110 / Official Journal C 247 E , 31/08/1999)

‘Where the jurisdiction of the court first seised is established, the court second seised shall decline jurisdiction in favour of that court. In that case, the party who brought the relevant action before the court second seised may bring that action before the court first seised’.

It should be emphasised that, under this rule, the court second seised must always decline jurisdiction in favour of the court first seised, even when the internal law of that Member State does not provide for separation or annulment.

’57 (…)( That would be the case, for instance, if an application for divorce were presented in Sweden and an application for annulment in Austria: the Austrian court would have to decline jurisdiction even though Swedish law makes no provision for annulment. Once the divorce ruling was final in Sweden, however, the interested party could apply to a court in Austria, in order to ensure that those effects of the divorce which would be null under Austrian law would have the necessary effects ex tunc as opposed to divorce which has only effects ex nunc, bearing in mind, moreover, that the recognition of the scope of this Convention is restricted to changes in civil status (see paragraph 64). The same principle would apply to the reverse situation. That is to say that the [Regulation] will not prevent an Austrian judgment on annulment from being the object, in Sweden, of a subsequent court judgment to the effect that the annulment will have the effect of a divorce ruling in Sweden. The same problems would not, however, arise in relation to separation since, although Swedish law does not provide for it, divorce produces effects which are more extensive than and superimposed on the effects of separation’ (Borras (1998) C 221/47)

Article 20 of the Brussels II Regulation

Provisional, including protective, measures [Article 20 BR II] ![]()

Article

20 Provisional and protective measures |

‘In urgent cases, the provisions of this Regulation shall not prevent the courts of a Member State from taking such provisional, including protective, measures in respect of persons or assets in that State as may be available under the law of that Member State, even if, under this Regulation, the court of another Member State has jurisdiction as to the substance of the matter’ (Article 20, paragraph 1, BR II). This also applies to urgent situations relating to parental responsibility, in which the courts of the Member State where the child is present or his assets are located should be able to take the necessary measures to protect the child's person or property. However, for cases of child abduction a different regime is foreseen in Article 11, paragraph 3, BR II for the provisional protection of the child is for cases of child abduction.

‘As regards the rule on provisional and protective measures, it must be observed that it is not subject to the jurisdictional rules of the Regulation because it refers to proceedings encountered within its scope and is based on national law jurisdiction. The provision makes it clear that such measures may be adopted in one State even though the court of another State has jurisdiction to hear the case. Moreover, this Article applies only to urgent cases.

As to the content of the provision, it should be noted that although provisional and protective measures may be adopted in connection with proceedings within the scope of the Regulation and are applicable only in urgent cases, they relate to both persons and to property and therefore touch on matters not covered by the Regulation, in the case of actions provided for in national rules. The measures to be adopted are very broad since they can affect both persons and assets in the State in which they are adopted, something which is very necessary in matrimonial disputes. The Regulation says nothing about the type of measures or about their connection with the matrimonial proceedings. These measures, accordingly, affect even matters that do not come within the scope of the Regulation. This is a rule which enshrines national law jurisdiction, thereby derogating from the rules laid down in the first part of the Regulation. The provision makes it clear that such measures may be adopted in one State even though the court of another State has jurisdiction to hear the case. The measures will, of course, cease to apply once the court having jurisdiction gives a judgment on the basis of one of the grounds of jurisdiction set out in the Regulation and that judgment is recognised (or enforced) under the Regulation. Other measures relating to matters excluded from the scope of the Regulation will continue to apply until appropriate judgments are given by a court with jurisdiction for, for example, marriage contracts’ (COM/99/0220 final - CNS 99/0110 / Official Journal C 247 E , 31/08/1999 and Borras (1998) C 221/47-48)

The rule laid down in Article 20, paragraph 1, BR II is confined to establishing territorial effects in the State in which the measures are adopted. In addition, paragraph 2 of Article 20 BR II provides that these measures shall cease to apply once the courts having jurisdiction as to the substance of the matter have taken a decision it considers appropriate.

The European Court has indicated that a protective measure, such as the taking into care of children, may be decided by a national court under Article 20 of the Brussels II Regulation (No 2201/2003), if the following conditions are satisfied:

-

the measure must be urgent;

-

it must be taken in respect of persons in the Member State concerned, and

-

it must be provisional.

The taking of that measure, adopted in the best interests of the child and its binding nature are determined in accordance with national law. After the protective measure has been taken, the national court is not required to transfer the case to the court of another Member State having jurisdiction. However, since provisional or protective measures are temporary, circumstances related to the physical, psychological and intellectual development of the child may require early intervention by the court having jurisdiction in order for definitive measures to be adopted. Therefore, in so far as the protection of the best interests of the child so require, the national court which has taken provisional or protective measures must inform, directly or through the central authority designated under Article 53 BR II, the court of another Member State having jurisdiction (see paras 47, 56, 59, 64-65, operative part 3). Where the court of a Member State does not have jurisdiction at all, it must declare of its own motion that it has no jurisdiction, but is not required to transfer the case to another court. However, in so far as the protection of the best interests of the child so requires, the national court which has declared of its own motion that it has no jurisdiction must inform, directly or through the central authority designated under Article 53 of the Brussels II Regulation the court of another Member State having jurisdiction (ECJ 2 April 2009, Case C-523/07, ECR 2009 Page I-02805).

However, a court of a Member State in which a child is present cannot provisionally grant custody of the child to one parent if a court of another Member State, which has jurisdiction as to the substance of the case, has already given custody to the other parent. To accept that there was a situation of urgency in such a case would run counter to the principle of mutual recognition of judgments given in the Member States and to the legislature’s aim of deterring the wrongful removal or retention of children between Member States (ECJ 23 December 2009 ‘Jasna Deticek v Maurizio Sgueglia’, Case C-403/09 PPU).

The provisions of Article 19, paragraph 2, BR II does not lead to a stay of proceedings (in case of parental responsibility relating to the same child and involving the same cause of action are brought before courts of different Member States) where a court of a Member State first seised for the purpose of obtaining measures in matters of parental responsibility is seised only for the purpose of its granting provisional measures within the meaning of Article 20 of that Regulation and where a court of another Member State which has jurisdiction as to the substance of the matter within the meaning of the same regulation is seised second of an action directed at obtaining the same measures, whether on a provisional basis or as final measures. The fact that a court of a Member State is seised in the context of proceedings to obtain interim relief or that a judgment is handed down in the context of such proceedings and there is nothing in the action brought or the judgment handed down which indicates that the court seised for the interim measures has jurisdiction within the meaning of the Brussels II Regulation does not necessarily preclude the possibility that, as may be provided for by the national law of that Member State, there may be an action as to the substance of the matter which is linked to the action to obtain interim measures and in which there is evidence to demonstrate that the court seised has jurisdiction within the meaning of that regulation (ECJ 9 November 2010 ‘Bianca Purrucker v Guillermo Vallés Pérez’, Case C-296/10).