The Brussels II Regulation 2003

CHAPTER I SCOPE OF THE BRUSSELS II REGULATION

Index Chapter I

History of the Brussels II Regulation 2003

The foundation of the European Community’s private international law policy is the 1968 Brussels Convention on Jurisdiction and the Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters. Its function was to make sure that national judgments of Member States were recognized by other Member States and that they could be enforced there. It also regulated the question which country had jurisdiction in legal disputes between citizens of different Member States. The purpose was to create a free movement of judgments, which would help to build a free internal market. This Convention however was restricted to ‘civil and commercial matters’ (including maintenance). Matrimonial matters (divorce, legal separation, marriage annulment, parental responsibility and child abduction) were excluded, like moreover is still the case with its descendant, the Brussels I Regulation, which is as well limited to civil and commercial matters. The national laws of the Member States concerning matrimonial matters were found to be mutually incompatible and mostly of mandatory law, so - it was believed - that it would be too hard to unify the jurisdiction rules of the Member States on this field of law.

Nevertheless the need for a uniform European regulation for matrimonial matters was felt. Marriages between citizens of different Member States became more common. The first proposals for a European Convention were restricted to jurisdiction and enforcement of judgments with regard to divorce, legal separation and nullity. They didn’t cover jurisdiction and the enforcement of judgments relating to custody and connected orders, moreover since these subjects were already under consideration by the Hague Conference, which aimed at a worldwide solution for private international law issues affecting children. In 1996 these considerations led indeed to the 1996 Hague Convention on Jurisdiction, Applicable Law, Recognition, Enforcement and Co-operation in Respect of Parental Responsibility and Measures for the Protection of Children.

Prior to the Treaty of Amsterdam the European Union had no direct competences regarding Justice and Legal Affairs. Decisions taken in these matters could not be legalized directly in a European Regulation, but had to be carried out by means of a Convention between all participating Member States. This changed drastically after the Treaty of Amsterdam. Some matters concerning international private law were brought under the direct competence of the European Union itself, so that as from that moment the European Commission and the European Parliament were able to issue European Regulations on this field of law with immediate effect in the Member States, although Member States had a right to opt-out. It was not longer necessary to put the decision in a Convention, which in fact was a separate treaty that had to be accepted by all Member States. The result of this change was that the Brussels II Convention regarding matrimonial matters, that already was accepted by the Member States, but not yet ratified, ended before it even came into force. It was replaced in 2001 by a Regulation of the European Union, which enclosed almost the same rules as the Brussels II Convention. Just like this Convention, this so-called Brussels II Regulation was modeled on the Brussels I Regulation concerning civil and commercial matters. The Borras report clarifies that, where the terms in Brussels I and II are identical, they must be given the same meaning with case law from the European Court of Justice being used as a tool for interpretation (The Borras Report (1998) O J C 221/27, the Explanatory Report on Brussels II).

The Brussels II Regulation came into force on 1 March 2001 and regulated jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in matrimonial matters (divorce, legal separation, marriage annulment itself) and in matters of parental responsibility for joint children. It bounded all the EU Member States except Denmark. But soon new aims were pursued. The plan was to extend the rules on mutual recognition and enforcement of Brussels II to all decisions on parental responsibility. Furthermore the European Commission wanted to reinforce the obligation of the courts to order the return of children abducted within the Community. Also the fundamental principle, that the most appropriate forum for matters of parental responsibility is the state of the child’s habitual residence, had to be strengthened. These aims lead to a revision of the existing Brussels II Regulation. A new Brussels II Regulation came into force on 1 August 2004 and applies from 1 March 2005 (No. 2201/2003 (EC). It repeals the existing Brussels II Regulation and too binds all EC states with the exception of Denmark. It has been referred to variously as Brussels II Bis or B or Brussels IIA or the new Brussels II.

The new Brussels II Regulation (or the Brussels II Regulation 2003) is to a large extent a copy of the old Brussels II Regulation of 2001, that is to say as far as divorce and other matrimonial matters are concerned but, as to parental responsibility, it now covers all children, rather than only children of both spouses and it presents new provisions regarding abduction, which expand and take precedence over the 1980 Hague Convention in cases between the subscribing Members of the European Union. But it has to be observed that the Brussels II Regulation only deals with questions relating to jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments on divorce (including legal separation and marriage annulment), abduction and custody. It is therefore restricted to issues on the field of international private law. It does not apply to issues such as the grounds for divorce or the property consequences of the marriage or other ancillary relief. Nor does the Brussels II Regulation deal with the question of applicable law. These questions have to be answered using the national law of the different Member States, which usually means that the Member State with jurisdiction according to its own rules of international private law on this field, including the Brussels II Regulation, applies its own law and sometimes the law of the country of the Respondent. Moreover the Brussels II Regulation doesn’t apply to matters governing jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments with regard to maintenance obligations, which are dealt with separately by the Brussels Regulation (Council Regulation 44/2001).

Geographical scope of the Brussels II Regulation 2003

The Brussels II Regulation applies as of 1 March 2005 in all Member States of the European Union, with the exception of Denmark. Consequently it also applies in the ten Member States which joined the European Union on 1 May 2004. The Regulation is directly applicable in the Member States and prevails over national law (Art. 72 Practice Guide 2005). Again it has to be said that the Regulation is restricted to issues of International Private Law on the field of family law. It points out which Member State has jurisdiction to proclaim a divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment or to rule over parental responsibility and child abduction. It also contains rules on how to get such judgments recognized and even enforceable in other Member States. But it does not apply to issues such as the grounds for divorce or the property consequences of the marriage or other ancillary relief. Nor does the Brussels II Regulation deal with the question of applicable law. These questions still have to be answered using the national law of the different Member States.

Article 1 of the Brussels II Regulation

- Material scope of the Brussels II Regulation: civil and commercial matters [Art. 1(1) BR II]

- Type of proceedings covered by the Brussels II Regulation [Art. 1(1) BR II]

- Subject-matters covered by and excluded

from the Brussels II Regulation [Art. 1(2)(3) BR II]

- Breaking the marriage link through a divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment by judgment [Art. 1(1)(a) BR II]

- Attribution, exercise, delegation, restriction or termination of parental responsibility [Art. 1(1) and (2) BR II]

- Protective measures concerning the property of the child provided their aim is to protect the child [Art. 1 (2) (c) and (e) BR II]

Index Article 1

Material scope of the Brussels II Regulation [Article

1 BR II] ![]()

Article

1 Scope |

Article 1 BR II defines both the type of proceedings to which the Regulation applies and their subject matter. In addition to civil judicial proceedings, the scope of the Regulation also includes other non-judicial proceedings occurring in matrimonial matters in certain States. Administrative procedures officially recognised in a Member State are therefore included. This excludes all merely religious proceedings.

The term ‘civil matters’ within the meaning of Article 1, paragraph 1, BR II, has to be interpreted autonomously. Only the uniform application of the Brussels II Regulation in the Member States, which requires that the scope of that Regulation be defined by Community law and not by national law, is capable of ensuring that the objectives pursued by that Regulation are attained in all Member States equally (ECJ 27 November 2007 ‘Nordic States’, Case C-435/06 and ECJ 5 October 2010 ‘J. McB. v L.E.’, Case C-400/10 PPU).

The reference to 'courts', in paragraph 1, includes all the authorities, judicial or otherwise, with jurisdiction in matrimonial matters. The term 'civil proceedings' encompasses not only judicial but also administrative proceedings where available under national law.

Paragraph 1 is confined to proceedings relating to the marriage link as such, i.e. annulment, divorce and legal separation. So the recognition of divorce and annulment rulings affects only the dissolution and annulment of the marriage link. Despite the fact that they may be interrelated, the Regulation does not affect issues such as, for example, fault of the spouses, property consequences of the marriage, the maintenance obligation or other possible accessory measures (such as the right to a name, etc.).

The question of parental responsibility had to be included in the scope of the Regulation, since in some States the legal system requires that the decision on matrimonial matters includes parental responsibility. The concept of 'parental responsibility' has to be defined by the legal system of the Member State in which responsibility is under consideration.

Innitially the term 'parental responsibility' was confined to the 'children of both spouses', in view of the fact that the context was that of measures relating to parental responsibility taken in close conjunction with divorce, separation or annulment proceedings (COM/99/0220 final - CNS 99/0110 / Official Journal C 247 E , 31/08/1999). Yet, by Proposal 2002 the scope of Council Regulation (EC) No 1347/2000 has been extended to cover all civil proceedings relating to parental responsibility by severing the link with the matrimonial proceedings. Still, matters relating to maintenance are excluded, as these are already covered by Council Regulation (EC) No 44/2001 (Brussels I Regulation), which offers a more advanced system of recognition and enforcement.

Moreover, it appears that in some Member States there is a clear separation between criminal measures and subsequent civil measures of protection, such as the placement of the child in an institution. Thus an exclusion from the scope is also provided to make clear that the Member State that takes the criminal measures would not be precluded by virtue of this Regulation from exercising jurisdiction to also take the required civil measures (Proposal 2002 OJ C 203E , 27.8.2002, p. 155–178). 1.

The European Court has considered that the term ‘civil matters’ within the meaning of Article 1, paragraph 1, BR II, has to be interpreted autonomously. Only the uniform application of the Brussels II Regulation in the Member States, which requires that the scope of that Regulation be defined by Community law and not by national law, is capable of ensuring that the objectives pursued by that Regulation, one of which is equal treatment for all children concerned, are attained. According to the fifth recital of the Brussels II Regulation, that objective can only be safeguarded if all decisions on parental responsibility fall within the scope of that Regulation. Parental responsibility is given a broad definition in Article 2, paragraph 7, BR II, inasmuch as it includes all rights and duties relating to the person or the property of a child which are given to a natural or legal person by judgment, by operation of law or by an agreement having legal effect. It is irrelevant in that respect whether parental responsibility is affected by a protective measure taken by the State or by a decision which is taken on the initiative of the person or persons with rights of custody (ECJ 27 November 2007 ‘Nordic States’, Case C-435/06). This means that a decision ordering that a child be immediately taken into care and placed outside his original home is covered by the term ‘civil matters’, for the purposes of that provision, even where that decision was adopted in the context of public law rules relating to child protection (ECJ 2 April 2009, Case C-523/07, ECR 2009 Page I-02805).

Type of proceedings covered by the Brussels II Regulation [Article

1(1) BR II]

Article 1 BR II sets out the material scope of the Regulation. It defines both the type of proceedings to which the Regulation applies and their subject matter.

With regard to the type of legal proceedings, the Regulation applies to all judgments which subject is covered by it, whatever the nature of the court or tribunal. This means that, in addition to civil judicial proceedings, the scope of the Regulation also includes other non-judicial proceedings occurring in matrimonial matters in certain States. Administrative procedures officially recognised in a Member State are therefore included. But the result is also that all merely religious proceedings are excluded. Article 2 BR II 2003 specifies that the reference to 'courts' includes all the authorities, judicial or otherwise, with jurisdiction in matrimonial matters.

‘A. In addition to civil judicial proceedings, the scope of the [Regulation] also includes other non-judicial proceedings occurring in matrimonial matters in certain States. Administrative procedures officially recognised in a Member State are therefore included. In Denmark, for instance, there is, in addition to the judicial course of action, an administrative procedure before the Statsamt (District Council) or before the Københavns Overpræsidium (which performs the same functions as the Statsamt for Copenhagen). For that procedure to apply, there must be grounds for divorce and agreement between the spouses both on the divorce and on matters connected with it (custody, maintenance, etc.). Appeals against the judgments given by the Statsamt and the Københavns Overpræsidium lie to the Ministry of Justice (Civil Law Directorate) and may then be subject to judicial review through the normal procedure. In the same way, it may be noted that in 1983 Finland adopted a system under which matters relating to custody, residence and visiting may be settled outwith the legal proceedings by agreement that must be approved by the ‘kunnan sosiaalilautakunta/ kommunal socialnämnd’ (communal social (welfare) board): ‘Laki lapsen huollosta ja tapaamisoikeudesta’/‘Lag angående vårdnad om barn och umgängesrätt’, Law 361 of 8 April 1983, Sections 7, 8, 10, 11 and 12). For that reason, the text stipulates, as did Article 1 of the 1970 Hague Convention on the recognition of divorces and legal separations, that the term ‘court’ shall cover all the authorities, judicial or otherwise, with jurisdiction in matrimonial matters in the Member States’ (Borras (1998) C 221/35).

Subject-matters covered by and excluded from the Brussels II Regulation

[Article 1(2)(3) BR II]

The Regulation applies to “civil matters”. The concept of “civil matters” is broadly defined for the purposes of the Regulation and covers all matters listed in Article 1(2). Where a specific matter of parental responsibility is a “public law” measure according to national law, e.g. the placement of a child in a foster family or in institutional care, the Regulation shall apply’ (Practice Guide 2005-06-01, p. 8). It concerns matters in relation to:

- breaking a marriage link through a divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment by judgment;

- judgments on the attribution, exercise, delegation, restriction or termination of parental responsibility;

- protective measures concerning the property of the child provided their aim is to protect the child;

Article 1(3) BR II 2003 enumerates those matters which may be closely linked to matters of parental responsibility (e.g. adoption, emancipation, the name and forenames of the child), but which have to be excluded from its scope for various reasons. The Brussels II Regulation explicitly does not apply to:

- the establishment or contesting of a parent-child relationship;

- decisions on adoption, measures preparatory to adoption, or the annulment or revocation of adoption;

- the name and forenames of the child;

- emancipation;

- maintenance obligations;

- trusts or succession;

- measures taken as a result of criminal offences committed by children.

The exclusion, mentioned in Article 1 (3) (g), is the result of the fact that in some Member States there appears to be a clear separation between criminal measures and subsequent civil measures of protection, such as the placement of the child in an institution. Thus an exclusion from the scope is also provided to make clear that the Member State that takes the criminal measures would not be precluded by virtue of this Regulation from exercising jurisdiction to also take the required civil measures.

In recital 11 of the Brussels II Regulation extra attention has been given to maintenance obligations. ‘Maintenance obligations and parental responsibility are often dealt with in the same court proceeding. Maintenance obligations are, however, not covered by the Regulation, since they are already governed by the Brussels I Regulation. A court which is competent pursuant to the Regulation will nevertheless generally have jurisdiction to rule also on maintenance matters by application of Article 5 (2) of the Brussels I Regulation. This provision allows a court which is competent to deal with a matter of parental responsibility also to decide upon maintenance if that question is ancillary to the question of parental responsibility. Although the two issues would be dealt with in the same proceeding, the resultant decision would be recognised and enforced according to different rules. The part of the decision relating to maintenance would be recognised and enforced in another Member State pursuant to the rules of the Brussels I Regulation whereas the part of the decision relating to parental responsibility would be recognised and enforced pursuant to the rules of the new Brussels II Regulation (Practice Guide 2005-06-01, p. 9).

Breaking the marriage link through a divorce, legal separation or marriage

annulment by judgment [Article 1(1)(a) BR II]

The Regulation is applicable to proceedings relating to the marriage link as such, i.e. annulment, divorce and legal separation. But the recognition of divorce and annulment rulings affects only the dissolution and annulment of the marriage link. Despite the fact that they may be interrelated, the Regulation does not affect issues such as, for example, fault of the spouses, grounds for divorce, property consequences of the marriage, the maintenance obligation or other possible accessory measures (such as the right to a name, etc.). Commission's Memorandum 1999: Article 1 - Scope [= Art. 1 BR 2003]. These issues are dealt by the national law of the Member States. Matters relating to maintenance are excluded, as these are already covered by Brussels I Regulation (Council Regulation (EC) No 44/2001), which offers a more advanced system of recognition and enforcement.

Attribution, exercise, delegation, restriction or termination of parental

responsibility [Article 1(1) and (2) BR II]

The question of parental responsibility had to be included in the scope of the Regulation, since in some States the legal system requires that the decision on matrimonial matters includes parental responsibility. In the old Brussels II Regulation the rules of parental responsibility were confined to the children of both spouses, in view of the fact that the context was that of measures relating to parental responsibility taken in close conjunction with divorce, separation or annulment proceedings. The new Regulation extends the scope and covers all civil proceedings relating to parental responsibility. A general definition of the term 'parental responsibility' is provided. The term ‘parental responsibility' means, according to Article 2 (7) BR II 2003, all rights and duties relating to the person or the property of a child which are given to a natural or legal person by judgment, by operation of law or by an agreement having legal effect. The term incorporates all rights of custody and rights of access. The right of custody includes rights and duties relating to the care of the person of a child and in particular the right to determine the child’s place of residence. The right of access includes in particular the right to take a child to a place other than his or her habitual residence for a limited period of time. So the term ‘parental responsibility' encompasses also matters such as guardianship and the placement of a child in a foster family or in institutional care. The holder of parental responsibility may be a natural or a legal person.

This definition of ‘parental responsibility’ is broad, since

it was felt to be important not to discriminate between children by excluding

certain measures and thus leaving certain children and situations outside

the scope of the Regulation. Hence the term relates to both the person

and the property of the child, while a holder of parental responsibility

may be either a natural or a legal person. The relevant rights and duties

may be acquired by judgment, by operation of law or by an agreement having

legal effect. It is further specified that the term includes rights of

custody and rights of access.

The matters referred to in paragraph 1(b) may, in particular, deal with:

- rights of custody and rights of access;

- guardianship, curatorship and similar institutions;

- the designation and functions of any person or body having charge of the child's person or property, representing or assisting the child;

- the placement of the child in a foster family or in institutional care and;

- measures for the protection of the child relating to the administration, conservation or disposal of the child's property.

‘The list of matters qualified as “parental responsibility” pursuant to the Regulation in Article 1 (2) BR II is not exhaustive, but merely illustrative. In contrast to the 1996 Hague Convention on child protection (See chapter XI), the Regulation does not define a maximum age for the children who are covered by the Regulation, but leaves this question to national law. Although decisions on parental responsibility concern in most cases minors below the age of 18, persons below 18 years may be subject to emancipation under national law, in particular if they marry. Decisions issued with regard to these persons do not in principle qualify as matters of “parental responsibility” and consequently fall outside the scope of the Regulation’ (Practice Guide 2005-06-01, p. 8).

Protective measures concerning the property of the child provided their

aim is to protect the child [Article 1 (2) (c) and (e) BR II]

The rule under (c) cannot be found in Article 1 BR II as a separate provision. Yet, it can be subtracted from the examples in the list of Article 1 (2) (c) and (e) and from recital 9. ‘When a child owns property, it may be necessary to take certain protective measures, e.g. to appoint a person or a body to assist and represent the child with regard to the property. The Regulation applies to any protective measure that may be necessary for the administration or sale of the property. Such measures may be necessary if, for instance, the child’s parents are in dispute as regards such a question’ (Practice Guide 2005-06-01, p. 9). Recital 9 explains: ‘As regards the property of the child, the Regulation should apply only to measures for the protection of the child, i.e. (i) the designation and functions of a person or body having charge of the child's property, representing or assisting the child, and (ii) the administration, conservation or disposal of the child's property (see the above list under c and e). In this context, this Regulation should, for instance, apply in cases where the parents are in dispute as regards the administration of the child's property. Measures relating to the child's property which do not concern the protection of the child should continue to be governed by Council Regulation (EC) No 44/2001 of 22 December 2000 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters (Brussels I Regulation)’. So, measures that relate to the child’s property, but which do not concern the protection of the child, are not covered by the Brussels II Regulation, but by Council Regulation No. 44/2001 of 22 December 2000 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters (the Brussels I Regulation). ‘It is for the judge to assess in the individual case whether a measure relating to the child’s property concerns the protection of the child or not. Whilst the Regulation applies to protective measures, it does not apply to measures taken as a result of criminal offences committed by children (Recital 10)’ (Practice Guide 2005-06-01, p. 9).

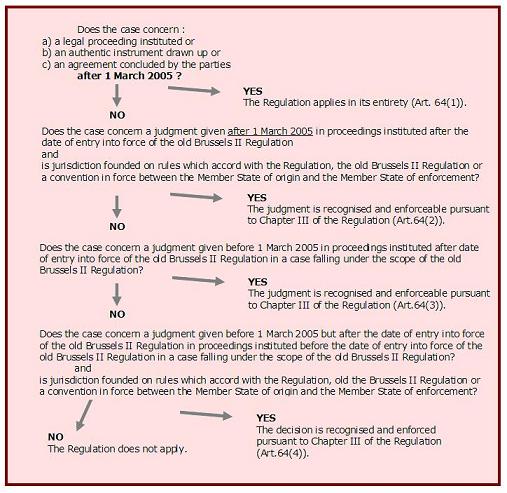

Transitional law [Article 64 BR II]

Article 64 BR II 2003 states that the provisions of this Regulation shall apply only to legal proceedings instituted, to documents formally drawn up or registered as authentic instruments and to agreements concluded between the Parties to the Regulation after its date of application in accordance with Article 72 BR II 2003. So all legal proceedings that are started after 1 March 2005 fall directly under the scope of the Brussels II Regulation 2003, of course provided they are covered by it. The same goes for documents formally drawn up or registered as authentic instruments after 1 March 2005 and agreements concluded between parties after 1 March 2005.

With respect to judgments ruled in legal proceedings that were instituted before 1 March 2005, the Brussels II Regulation 2003 is not directly applicable. There is, however, provision for the possibility of allowing a judgment to benefit from the system of the new Regulation, even if the action was brought before its entry into force (thus before 1 March 2005). One has to notice that the old Brussels II Regulation still can be of influence in these situations, insofar the legal proceeding was started before this Regulation became effective. It entered into force on 1 March 2001 for the old Member States, whereas for the ten new Member States, which joined the European Union on 1 May 2004, the relevant date to determine the entry into force of the old Brussels II Regulation is 1 May 2004.

Article 64 of the Brussels II Regulation 2003 contains rules of transitional law with respect to judgments in legal proceedings that were instituted before 1 March 2005 (which are thus not directly covered by the new Brussels II Regulation 2003), but that can benefit of the system of the new Regulation, provided certain conditions are met. It distinguishes three possibilities, depending on the moment on which these legal proceedings were started and on the moment on which the judgments in these legal proceedings were given: before the old Brussels II Regulation entered into force or afterwards, but prior to 1 March 2005, when the new Brussels II Regulation became effective? The rules on recognition and enforcement of the Regulation 2003 apply, in relation to legal proceedings instituted before 1 March 2005, to three categories of judgments:

- judgments given on or after 1 March 2005 in legal proceedings instituted before that date, but after the date of entry into force of the old Brussels II Regulation (1 March 2001 old Member Statse/1 May 2004 new Member States)

- judgments given before 1 March 2005 in legal proceedings instituted after the date of entry into force of the old Brussels II Regulation in cases which relate to divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment or parental responsibility for the children of both spouses on the occasion of these matrimonial proceedings;

- judgments given before 1 March 2005 but after the entry into force of the old Brussels II Regulation in proceedings instituted before the date of entry into force of the old Brussels II Regulation;

When the legal proceeding started under the scope of the old Brussels II Regulation, therefore after 1 March 2001 in one of the old Member States and after 1 May 2004 in one of the new Member States, it’s important to detect whether the judgment was ruled before the new Brussels II Regulation 2003 entered into force (1 March 2005) or afterwards. A judgement given after 1 March 2005 shall be recognised and enforced in accordance with the provisions of Chapter III of the Brussels II Regulation 2003 if jurisdiction was founded on rules which accorded with those provided for either in Chapter II of the new Brussels II Regulation 2003 or in the old Brussels II Regulation 2000 (No 1347/2000) or in a convention concluded between the Member State of origin and the Member State addressed which was in force when the legal proceedings were instituted (Art. 64 (2) BRII);

When the legal proceeding started under the scope of the old Brussels II Regulation, therefore after 1 March 2001 in one of the old Member States and after 1 May 2004 in one of the new Member States, but its judgment was ruled before the new Brussels II Regulation entered into force (1 March 2005), this judgment shall be recognised and enforced in accordance with the provisions of Chapter III of the new Brussels II Regulation 2003, provided they relate to divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment or parental responsibility for the children of both spouses on the occasion of these matrimonial proceedings, therefore only to matters which fell under the scope of the old Brussels II Regulation 2000 (Article 64(3) BR II);

When the legal proceeding has started even before the old Brussels II Regulation entered into force, therefore before 1 March 2001 in one of the old Member States and before 1 May 2004 in one of the new Member States, it’s important to detect whether the judgment was given before or after this Regulation (thus the old Brussels II) entered into force. A judgment in such a legal proceeding that is given when the old Brussels II Regulation was already effective, but before 1 March 2005, shall be recognised and enforced in accordance with the provisions of Chapter III of the new Brussels II Regulation (2003), provided they relate to divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment or parental responsibility for the children of both spouses on the occasion of these matrimonial proceedings and that jurisdiction was founded on rules which accorded with those provided for either in Chapter II of the new Brussels II Regulation or in the old Brussels II Regulation (No 1347/2000) or in a convention concluded between the Member State of origin and the Member State addressed which was in force when the proceedings were instituted (Article 64(4) BR II ). If the legal proceeding was instituted before the old Brussels II Regulation entered into force, but its judgment was given after the date of application of the new Brussels II Regulation (thus after 1 March 2005), the situation is not covered by Article 64 BR II.

Judgments falling under categories (a) to (c) are recognised and enforced pursuant to Chapter III of the new Brussels II Regulation, but this only under the following conditions:

- the court that handed down the judgment founded its jurisdiction on rules which accord with the new Brussels II Regulation, the old Brussels II Regulation or a convention which is applicable between the Member State of origin and the Member State of enforcement;

- and, for judgments given before 1 March 2005, provided they relate to divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment or parental responsibility for the children of both spouses on the occasion of these matrimonial proceedings.

It should be noted that in that event Chapter III on recognition and enforcement of the new Brussels II Regulation will apply in its entirety to these judgments, including the new rules in Section 4 thereof which dispenses with the exequatur procedure for certain types of judgments (see chapters VI and VII BR II).

| Example: |

Subject to the factual assessment which is a matter for the national court

alone, the Brussels II Regulation (No 2201/2003) is to be interpreted

as applying ratione temporis in a case such as that in the main

proceedings. It is clear from Articles 64(1) and 72 of that Regulation

that it applies only to legal proceedings instituted, to documents formally

drawn up or registered as authentic instruments and to agreements concluded

between the parties after 1 March 2005. Moreover, Article 64(2) of that

Regulation provides that judgments given after the date of application

of this Regulation in proceedings instituted before that date but after

the date of entry into force of Regulation No 1347/2000 shall be recognised

and enforced in accordance with the provisions of Chapter III of this

Regulation if jurisdiction was founded on rules which accorded with those

provided for either in Chapter II or in Regulation No 1347/2000 or in

a convention concluded between the Member State of origin and the Member

State addressed which was in force when the proceedings were instituted.

In a case such as that in the main proceedings, the Brussels II Regulation

(No 2201/2003) applies only if the three cumulative conditions listed

in the preceding paragraph of this judgment are fulfilled (ECJ

27 November 2007 ‘Nordic States’, Case C-435/06).

The Practice Guide (2005-06-01) provides a clear diagram of the steps that have to be followed in questions relating to the rules of transitional law of Article 64 BR II.

Cooperation between central authorities and between

courts [Articles 53 - 58 BR II]

An essential element of the Brussels II Regulation 2003 is a system of cooperation between central authorities covering both divorce and parental responsibility. Central authorities have a general information and coordination function, as well as cooperate in specific cases. This is especially important with regard to matters of parental responsibility. For this reason a specific Chapter (Chapter IV) is added to the Brussels II Regulation 2003.

Article 53 BR II 2003 orders each Member State to designate one central authority. These may be existing authorities entrusted with the application of international conventions in this area. ‘Each Member State shall designate one or more central authorities to assist with the application of this Regulation and shall specify the geographical or functional jurisdiction of each. Where a Member State has designated more than one central authority, communications shall normally be sent direct to the relevant central authority with jurisdiction. Where a communication is sent to a central authority without jurisdiction, the latter shall be responsible for forwarding it to the central authority with jurisdiction and informing the sender accordingly’.

‘The central authorities shall communicate information on national laws and procedures and take measures to improve the application of this Regulation and strengthening their cooperation. For this purpose the European Judicial Network in civil and commercial matters created by Decision No 2001/470/EC shall be used’ (Article 54 BR II 2003). In the first place, as members of the European Judicial Network, the central authorities work on an information system and discuss issues of common interest and their methods of cooperation. In this context they may also develop best practices on family mediation or facilitate the networking of organizations working in this area.

Most importantly, central authorities assume an active role for the purpose of ensuring the effective exercise of rights of parental responsibility in specific cases, within the limits placed on their action by national law. Hence, they share information, give advice, promote mediation, and facilitate court-to-court communications. They play a particularly important role in cases of child abduction, where they have an obligation to locate and return the child, including where necessary to institute proceedings for this purpose.

Article

55 BR II 2003 specifies how cooperation must take place in cases

specific to parental responsibility. ‘The central authorities shall,

upon request from a central authority of another Member State or from

a holder of parental responsibility, cooperate on specific cases to achieve

the purposes of this Regulation. To this end, they shall, acting directly

or through public authorities or other bodies, take all appropriate steps

in accordance with the law of that Member State in matters of personal

data protection to:

(a) collect and exchange information:

(i) on the situation of the child;

(ii) on any procedures under way; or

(iii) on decisions taken concerning the child;

(b) provide information and assistance to holders of parental responsibility

seeking the recognition and enforcement of decisions on their territory,

in particular concerning rights of access and the return of the child;

(c) facilitate communications between courts, in particular for the application

of Article

11(6) and (7) BR II 2003 and Article

15 BR II 2003;

(d) provide such information and assistance as is needed by courts to

apply Article

56 BR II 2003; and

(e) facilitate agreement between holders of parental responsibility through

mediation or other means, and facilitate cross-border cooperation to this

end’.

‘The central authorities will play a vital role in the application of the Regulation. The Member States must designate at least one central authority. Ideally, these authorities should coincide with the existing authorities entrusted with the application of the 1980 Hague Convention. This could create synergies and allow the authorities to benefit from the experiences acquired by the authorities in child abduction cases.

The central authorities must be given sufficient financial and human resources to be able to fulfil their duties and their personnel must receive adequate training before the entry into force of the Regulation. The use of modern technologies should be encouraged.

The Regulation foresees that the central authorities will be effectively integrated in the European Judicial Network on civil and commercial matters (European Judicial Network) and that they will meet regularly within this Network to discuss the application of the Regulation.The specific duties of the central authorities are listed in Article 55. They include facilitating court-to-court communications, which will be necessary in particular where a case is transferred from one court to another (See Chapters III and VII). In these cases, the central authorities will serve as a link between the national courts and the central authorities of other Member States.

Another task of the central authorities is to facilitate agreements between holders of parental responsibility through e.g. mediation. It is generally considered that mediation can play an important role in e.g. child abduction cases to ensure that the child can continue to see the non-abducting parent after the abduction and to see the abducting parent after the child has returned to the Member State of origin. However, it is important that the mediation process is not used to unduly delay the return of the child.

The central authorities do not have to carry out these duties themselves, but may act through other agencies.

In parallel with the requirements for central authorities to co-operate, the Regulation requires that the courts of different Member States co-operate for various purposes. Certain provisions impose specific obligations upon judges of different Member States to communicate and to exchange information in the context of a transfer of a case (see chapter III) and in the context of child abduction (see chapter VII).

To encourage and facilitate such co-operation, discussions between judges should be encouraged, both within the context of the European Judicial Network and through initiatives organised by the Member States. The experience of the informal “liaison judge arrangement” organised in the context of the 1980 Hague Convention may prove instructive in this context.

It may be that some Member States may consider it worthwhile to establish liaison judges or judges specialised in family law to assist in the functioning of the Regulation. Such arrangements, within the context of the European Judicial Network, could lead to effective liaison between judges and the central authorities as well as between judges, and thus contribute to a speedier resolution of cases of parental responsibility under the Regulation (Practice Guide 2005, p. 44-45).

Article 2 of the Brussels II Regulation

Definitions for the purposes of the Brussels II Regulation [Article 2 BR II]

Article

2 Definitions |

Article 2 BR II defines some important terms used in the Regulation.

'Court and Judgment': The definitions of the terms 'court' and 'judgment' correspond to Articles 1(2) and 13(1) of Council Regulation (EC) No 1347/2000 respectively.

'Member State': The Brussels II Regulation does not apply to Denmark, in conformity with the Protocol on the position of Denmark annexed to the Treaty on the European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community.

The Brussels II Regulation applies as of 1 March 2005 in all Member States of the European Union, with the exception of Denmark. Consequently it also applies in the ten Member States which joined the European Union on 1 May 2004. The Regulation is directly applicable in the Member States and prevails over national law (Art. 72 Practice Guide 2005). Again it has to be said that the Regulation is restricted to issues of International Private Law on the field of family law. It points out which Member State has jurisdiction to proclaim a divorce, legal separation or marriage annulment or to rule over parental responsibility and child abduction. It also contains rules on how to get such judgments recognized and even enforceable in other Member States. But it does not apply to issues such as the grounds for divorce or the property consequences of the marriage or other ancillary relief. Nor does the Brussels II Regulation deal with the question of applicable law. These questions still have to be answered using the national law of the different Member States.

'Member State of origin' and 'Member State of enforcement': The terms 'Member State of origin' and 'Member State of enforcement' are used to facilitate the reading.

'Parental responsibility': A general definition of the term 'parental responsibility' is provided. This definition is broad, as the Commission considers it important not to discriminate between children by excluding certain measures and thus leaving certain children and situations outside the scope of the Regulation.

Hence the term relates to both the person and the property of the child, while a holder of parental responsibility may be either a natural or a legal person. The relevant rights and duties may be acquired by judgment, by operation of law or by an agreement having legal effect. It is further specified that the term includes rights of custody and rights of access.

Parental responsibility is given a broad definition in Article 2, paragraph 7, BR II, inasmuch as it includes all rights and duties relating to the person or the property of a child which are given to a natural or legal person by judgment, by operation of law or by an agreement having legal effect. It is irrelevant in that respect whether parental responsibility is affected by a protective measure taken by the State or by a decision which is taken on the initiative of the person or persons with rights of custody (ECJ 27 November 2007 ‘Nordic States’, Case C-435/06). This means that a decision ordering that a child be immediately taken into care and placed outside his original home is covered by the term ‘civil matters’, for the purposes of that provision, even where that decision was adopted in the context of public law rules relating to child protection (ECJ 2 April 2009, Case C-523/07, ECR 2009 Page I-02805).

'Holder of parental responsibility': The term 'holder of parental responsibility' is used to facilitate the reading.

'Rights of custody': Contrary to common usage, a broad definition is given to the term 'rights of custody' to encompass any right to have a say in determining the child's place of residence. In fact, the definition follows closely Article 5 of the 1980 Hague Convention, [10] albeit using "have a say in determining" instead of "determine", which better reflects the case law under the Convention. The term is then used in the definition of child abduction, which is based on a breach of rights of custody. See also hereafter for the interpretation given by the European Court.

'Rights of access': This definition mirrors the definition in Article 5 of the 1980 Hague Convention.

'Child abduction': This definition mirrors the definition in Article 3 of the 1980 Hague Convention. This requires taking notice directly of the law or of a judgment of the Member State of the habitual residence of the child to determine whether a child abduction has taken place.

Article 2, paragraph 9, BR II defines ‘rights of custody’ as covering ‘rights and duties relating to the care of the person of a child, and in particular the right to determine the child’s place of residence’. Since ‘rights of custody’ is thus defined by the Brussels II Regulation it is an autonomous concept which is independent of the law of Member States. It follows from the need for uniform application of European Union law and from the principle of equality that the terms of a provision of that law which makes no express reference to the law of the Member States for the purpose of determining its meaning and scope, must normally be given an autonomous and uniform interpretation throughout the Union, having regard to the context of the provision and the objective pursued by the legislation in question (C-66/08 Kozlowski [2008] ECR I-6041, paragraph 42 and case-law cited). Accordingly, for the purposes of applying the Brussels II Regulation, rights of custody include, in any event, the right of the person with such rights to determine the child’s place of residence. An entirely separate matter, however, is the identity of the person who has rights of custody. In that regard, it is apparent from Article 2, paragraph 11, under (a), of the Brussels II Regulation that whether or not a child’s removal is wrongful depends on the existence of ‘rights of custody acquired by judgment or by operation of law or by an agreement having legal effect under the law of the Member State where the child was habitually resident immediately before the removal or retention’. It follows that the Brussels II Regulation does not determine which person must have such rights of custody as may render a child’s removal wrongful within the meaning of Article 2, paragraph 11, BR II, but refers to the law of the Member State where the child was habitually resident immediately before its removal or retention the question of who has such rights of custody. Accordingly, it is the law of that Member State which determines the conditions under which the natural father acquires rights of custody in respect of his child, within the meaning of Article 2, paragraph 9, BR II, and which may provide that his acquisition of such rights is dependent on his obtaining a judgment from the national court with jurisdiction awarding such rights to him. The result is that the Brussels II Regulation must be interpreted as meaning that whether a child’s removal is wrongful for the purposes of applying that regulation is entirely dependent on the existence of rights of custody, conferred by the relevant national law, in breach of which that removal has taken place (ECJ 5 October 2010 ‘J. McB. v L.E.’, Case C-400/10 PPU).